Maya Miriga Behind the scenes: Film Heritage Foundation

| Photo Credit: SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

With Shyam Benegal’s Manthan (1976) making it to the headlines, thanks to the screening of its restored version at the Cannes Film Festival recently, the idea of lost and re-membered stands at the cross-section of visual retelling of the forgotten. The organisation responsible for its restoration is set to hit the headlines again with the screening of celebrated Odia film director Nirad Mohapatra’s classic Maya Miriga (Mirage, 1984) at the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna, Italy, from June 22 to 30.

“Even though thefilm was out of circulation for a long time, it kept popping up in conversations over the years. As it happened, of the hundreds of films teetering on the verge of disappearing and clamouring to be restored, circumstances dictated that Maya Miriga make the list,” says Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, Director, Film Heritage Foundation.

A still from the 1984 Odiya classic Maya Miriga : Film Heritage Foundation

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

The critically acclaimed film would have never seen the light of today, if the director’s son Sandeep Mohapatra had not made earnest efforts to restore it. The work that began in 2021, from one restoration lab to another, came to fruition after three years and is now going to be accessible to connoisseurs of cinema.

Nirad Mohapatra, alumnus of the Film and Television Institute of India, adhered to Italian Neo-Realism and Indian New Wave schools of filmmaking. It is evident in his cinematic choices in Maya Miriga with amateur actors, real locations, lack of melodrama, realistic attires and improvisations. Nirad Mohapatra wrote in his blog in October 2012 that he was not very inclined towards focussing on ‘individuation’, rather he wanted to showcase the overarching narrative and characters who are a part of the story. “One of the reasons why I have not used any close-up in my film is of course to maintain an aesthetic distance but it is also to avoid overemphasis through psychological cutting,” he wrote.

Maya Miriga film repair stills: Film Heritage Foundation

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

The film stands at the crossroad of transition to modernisation while staying connected to one’s roots. The director subtly raises the questions of moving ahead and looking back. It is Mohapatra’s emotional attachment to the family as against freedom for oneself that provides the mainstay of its conflict, which arises from the social reality of the middle class.

A big joint family living in the semi-urban locality of Puri, Odisha witnesses muted rebellion as the questionof individual ambition and family values bog down the sons and the daughters-in-law. Two couples of the family stand at two extremes. The eldest son (Tuku) takes on the responsibility of looking after the family and educating his siblings while his wife (Prabha), though submissive, constantly questions his decisions but only behind closed doors. Prabha fits the archetype of an abiding and nurturing daughter in law. However, her glimmer in the eyes die down slowly as duty takes over dreams.

The second son Tutu aspires for a better quality of life. Post joining the bureaucracy, the couple decide to relocate to Delhi on the suggestion of his wife. While Tuku’s wife might be termed as the ‘villain’ here, however, as the principles of realism hold, it is time and circumstances that pose to be the real harbingers of change for the good or the worse. Mohapatra uses several symbols to say less and show more.

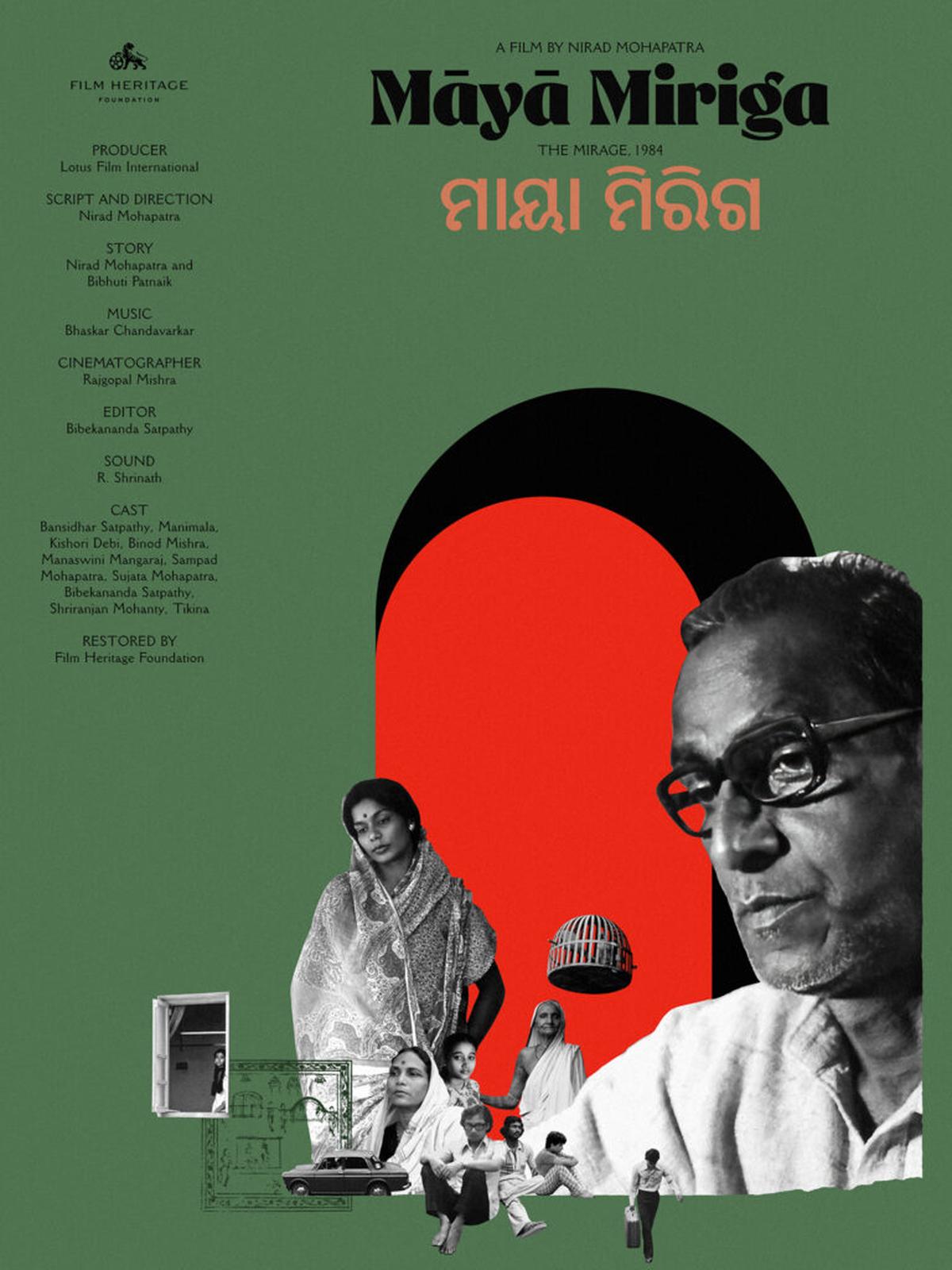

Maya Miriga poster : Film Heritage Foundation

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

Mohapatra uses several symbols to say less and show more. For instance, Prabha’s gaze towards the cages parrots shows her own limitations. The staircase of the house is depicted as a symbol of upward mobility which Prabha never climbs. In early scenes, Tutu comes from the city and brings a portrait of an English child wearing a frock. It is the director’s way of showing Tutu’s inclination to new age.

In terms of music, he uses one single Carnatic raga in the film that is being sung by a neighbour. The music comes and goes. Its liminality throughout the film strikes a chord in the viewer’s mind.

The film, made with a shoestring budget, won accolades but, eventually, got lost. Now, after so many years, it is still relevant. As Mohapatra said, “The balance that I ultimately wanted to achieve was between realism and simplicity on the one hand and my preoccupation with a certain cinematic form on the other.”